History of the Modern Oil Industry

Throughout human history, before the modern history of the oil and gas industry even begins, energy has been a key enabler of living standards.

To survive in the agrarian era, people burned wood for warmth and cooking. In addition to use as a building material, wood remained the chief global fuel for centuries.

The invention of the first modern steam engine, at the beginning of the 18th century, heralded the transformation from an agrarian to an industrial economy.

Steam engines could be powered by either wood or coal, but coal quickly became the preferred fuel and it enabled massive growth in the scale of industrialization.

A half-ton of coal produced four times as much energy as the same amount of wood and was cheaper to produce and, despite its bulk, easier to distribute.

Coal-fired steam locomotives dramatically reduced the time and cost of inland transportation, while steamships traversed oceans. Machines powered by coal enabled breakthroughs in productivity while reducing physical toil.

With the dawn of the 20th century, environmental concerns and new technologies led to another energy source shift from coal to oil.

Interestingly, although women were not yet allowed to vote, ladies’ societies in the United States were instrumental in lobbying for laws to improve air quality and reduce the dense smoke caused by burning coal.

Common History of Oil Questions:

When Was Oil Discovered?

The first oil had actually been discovered by the Chinese in 600 B.C. and transported in pipelines made from bamboo.

However, Colonel Drake’s heralded discovery of oil in Pennsylvania in 1859 and the Spindletop discovery in Texas in 1901 set the stage for the new oil economy.

Petroleum was much more adaptable and flexible than coal. Additionally, the kerosene that was refined originally from crude provided a reliable and relatively inexpensive alternative to “coal-oils” and whale oil for fueling lamps.

Most of the other products were discarded.

With the technological breakthroughs of the 20th century, oil emerged as the preferred energy source. The key drivers of that transformation were the electric light bulb and the automobile.

Automobile ownership and demand for electricity grew exponentially and, with them, the demand for oil.

By 1919, gasoline sales exceeded those of kerosene. Oil-powered ships, trucks and tanks, and military airplanes in World War I proved the role of oil as not only a strategic energy source, but also a critical military asset.

Prior to the 1920s, the natural gas that was produced along with oil was burned (or flared) as a waste by-product. Eventually, gas began to be used as fuel for industrial and residential heating and power.

As its value was realized, natural gas became a prized product in its own right.

What was the first oil company?

The first oil corporation was the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company which was formed to exploit oil found floating on water surfaces near Titusville, Pennsylvania the first successful oil well would later change the face of the oil industry forever.

Edwin Drake is often associated with the discovery of oil, but it was his association with the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company that sent him to the area to research and develop the possibility for the oil industry in the area.

The success of Edwin Drake’s oil well drilling operations in Titusville, however, would attract attention. Within a decade, John D. Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Company would come to dominate the oil industry both in Titusville and across the nation.

Who drilled the first oil well?

The first oil well known to tap oil at its source using this method was drilled by the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company in Titusville, Pennsylvania.

Edwin Drake was put in charge of developing oil industry potential in the area. It was Edwin Drake who had engaged William Smith, a well-regarded salt driller, to come to Titusville to oversee the drilling of the first oil well.

This first oil well was successfully drilled on August 27, 1859.

The success of this first oil well in Titusville would set off historical events, including the rapid formation of the Standard Oil Company.

It wouldn’t be until 1938 that the first oil well would be drilled in Saudi Arabia, tapping into what would soon be identified as the largest source of oil in the world.

Key Sources of Oil Industry Data

IEA – International Energy Agency

EIA – US Energy Information Administration

BP Statistical Review of World Energy

Who produces the most oil?

History of World Oil Production

Which country consumes the most oil?

Fossil Fuel Consumption by Country

Per Capita Oil Consumption

Who has the most oil in the world?

Venezuela has the largest oil reserves in the world estimated to be 300 billion barrels. This represents 18.2% of global oil reserves.

Venezuela is followed by Saudi Arabia and Canada.

Oil reserves by country below (in millions):

1. Venezuela 299,953 18.2%

2. Saudi Arabia 266,578 16.2%

3. Canada 170,863 10.4%

4. Iran 157,530 9.5%

5. Iraq 143,069 8.7%

6. Kuwait 101,500 6.1%

7. United Arab Emirates 97,800 5.9%

8. Russia 80,000 4.8%

9. Libya 48,363 2.9%

10. Nigeria 37,070 2.2%

11. United States 35,230 2.1%

*source

Learn more about our online oil and gas training courses.

History of Oil: Timeline of Key Events in the Oil Industry

1850 – Kerosene Gaslight Company was formed by Abraham Gesner, a Canadian geologist who developed a process to refine kerosene from coal. Kerosine burned more cleanly than whale oil, the dominant illumination fuel at the time.

1853 – An early commercial well is hand-dug in Poland

1853 – America’s first oil refinery built by Samuel Kier in Pittsburgh, PA

1857 – American Merrimac Company digs a “well” to 280 feet in Trinidad, Caribbean

1858 – James Miller Williams digs oil well in Oil Springs, Ontario, Canada

August 27, 1859 – First oil well drilled in Titusville, PA by Edwin Drake of the Pennsylvania Rock Oil Company

1866 – Oil production begins in Oil Springs, Texas

1867 – Rockefeller forms the Standard Oil Company

1870 – Standard Oil is the dominant refining company in Pennsylvania

1870 – Kerosine has replaced whale oil as the dominant fuel for illumination, bringing an end to the era of whale oil.

1880’s – Pennsylvania is producing 77% of the global oil supply. Russia would eclipse as the dominant producer by the 1900s.

1892 – Edward L. Doheny drills the first oil well in Los Angeles. Within five years there would be 2500 oil wells and two hundred oil companies in the area.

1894 – First significant Texas oil field developed near Corsicana and would eventually build the first modern refinery in Texas.

1900 – Standard Oil begins to operate in California

January 10, 1901 – Spindletop Geyser

The well-known Spindletop (actually named the Lucas No. 1 well) was a literal gusher of oil that had never been seen before in the United States. This discovery near Beaumont, Texas would set off the oil industry boom in Texas.

More than 1500 oil companies would be formed within a year of the Spindletop geyser.

1909 – Oil production in the United States surpassed that of the rest of the world combined.

1911 – US Supreme Court ordered the Standard Oil Trust to break apart. The monopoly would become thirty-four separate companies.

1938 – Discovery of oil in Saudi Arabia

1956 – Suez Crisis and nationalization of the Suez Canal by Egypt

1960 – OPEC formed in Baghdad, Iraq

1973-74 Arab oil embargo

1980s – Oil glut sends the price of oil from $35 a barrel to below $10

1989 – Exxon Valdez oil spill

1990 – Gulf War

1997 – Hydraulic fracturing (fracking) proliferates after the Mitchell Energy Company perfects the technique making it economically feasible.

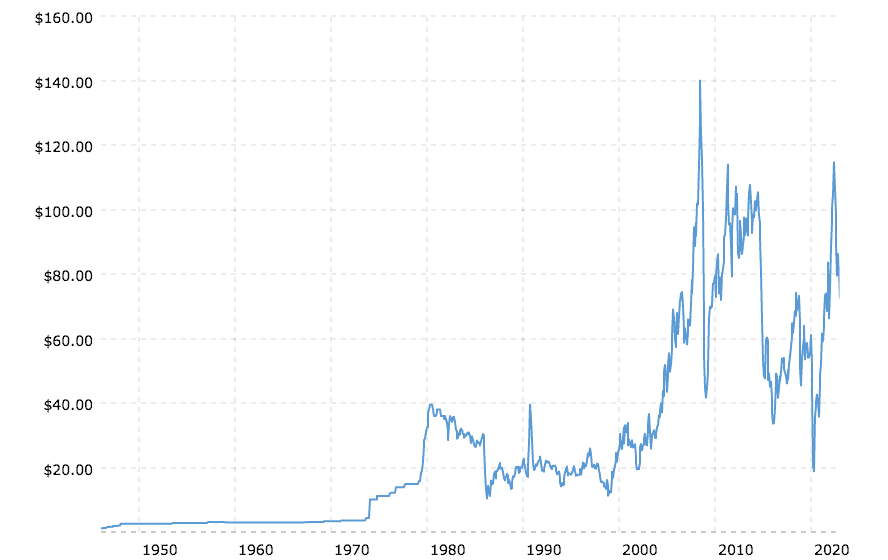

The 2000s – Oil prices spike. With prices for oil generally staying below $25 a barrel, prices hit $30 in 2003. The price of oil continues to climb above $65 in 2005 and eventually hits a high of $147.30 in 2008.

2008 – Global Financial Crisis – Just as oil prices are topping out at $147 a barrel, the global financial crisis sends economic demand into rapid decline.

2010 – BP Horizon oil spill

2015 – Oil Glut. The effectiveness and explosion of oil production in the US due to advancements in hydraulic fracturing leads to a global glut in oil supplies. The US lifts oil export ban that has been in place to strategically protect domestic oil reserves.

The impending oil price collapse would eventually lead to consolidation among oil industry producers.

History of Oil Prices

The first era showed an extremely volatile market that would not seem incongruent with a new market, a full-on (black) gold rush – that saw prices spike from near zero to over $7 a barrel before crashing back down by 1880.

By this time, the monopoly of Standard Oil had dominated the market for both oil and refined products, leading to a period of price stability (although not great for competition).

The fact that oil prices stayed so low for so long may be a better indicator of the profits Standard Oil reaped from refined products than what you might think was a lack of demand.

The second era in the history of oil prices shows almost no volatility or real price appreciation for almost 100 years, despite the well-documented demand growth from the industrial revolution.

Finally, the current volatile era of oil prices began in 1970 with the Arab Oil Embargo, the formation of OPEC, the evolution of hydraulic fracturing, and lasts to today.

History of Oil: The Major Companies Era

To understand how the oil and gas industry works, it is also important to understand how it has changed over time. The key factor in the industry development is who controls the key asset, the oil and gas reserves.

The history of the oil industry is one of the radical shifts in control and dominance.

Standard Oil, Royal Dutch Shell, and British Petroleum: The Original Super-Majors

John D. Rockefeller, who began his career in refining, became the industry’s first “baron” in 1865 when he formed Standard Oil Company. By 1879, Standard Oil controlled not only 90% of America’s refining capacity, but also its pipelines and gathering systems.

By the end of the 19th century, Standard Oil’s dominance had grown to include exploration, production, and marketing. Today ExxonMobil is the successor company to Standard Oil.

While Rockefeller was building his U.S. empire, the Nobel and Rothschild families were competing for control of production and refining of Russia’s oil riches.

In search of a global transportation network to market their kerosene, the Rothschilds commissioned the first oil tankers from a British trader, Marcus Samuel. The first of these tankers was named the Murex, after a type of seashell, and became the flagship of Shell Transport and Trading, which Samuel formed in 1897.

Royal Dutch Petroleum got its start in the Dutch East Indies in the late 1800s, and by 1892 had integrated production, pipelining, and refining operations. In 1907, Royal Dutch and Shell Transport and Trading agreed to form the Royal Dutch Shell Group.

Also in 1907, the discovery of oil in Iran by a British former gold miner and a Middle Eastern shah led to the incorporation of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company.

The British government purchased 51% of the company in 1914 to ensure sufficient oil for the Royal Navy in the years leading up to World War I. The company became British Petroleum in 1954 and is now BP.

Today, these three companies—ExxonMobil, Shell, and BP—are considered the original “supermajors.”

In the United States, the 1901 discovery of the Spindletop field in Texas eventually spawned companies such as Gulf Oil, Texaco, and others. The dominance of the United States during this era was illustrated by the fact that regardless of where oil was produced in the world, its price was fixed at that of the Gulf of Mexico.

Beginning with World War I, oil became a strategic energy source and a tremendous geopolitical prize. In the 1930s, Gulf Oil, BP, Texaco, and Chevron were involved in concessions that made major discoveries in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Libya.

Based on those discoveries, a cartel of seven companies was formed that controlled the world’s oil and gas business for much of the twentieth century. Known as the Seven Sisters, they included: Exxon (originally Standard Oil), Royal Dutch/Shell, BP, Mobil, Texaco, Gulf, and Chevron.

History of Oil: The OPEC Era

Beginning in the 1950s, numerous shifts occurred that transferred control over oil and gas production and pricing from “Big Oil” and oil-consuming countries to oil-producing countries.

The governments of many oil-producing nations, particularly in the Middle East and South America, saw the Integrated Oil Companies (IOCs) operating there as instruments of their countries of origin (usually the U.S. or European countries).

For both economical and geopolitical reasons, the leaders of the producing countries began asserting their authority for control of their countries’ oil and gas resources (and associated wealth).

To signify their newfound authority, in 1960 the governments of Venezuela, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq, and Iran founded the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) for the purpose of negotiating with IOCs on matters of oil production, oil prices, and future concession rights.

OPEC had little impact during its first decade of existence. The tide turned in the early 1970s with the confluence of rising energy demand, re-negotiation of terms of business in Libya by Muammar al-Qaddafi, and the fourth Arab-Israeli war.

This chart, OPEC Share of World Crude Reserves, illustrates the breadth and distribution of OPEC oil reserves. OPEC represents a considerable political and economical force. According to their estimates, 81% of the oil reserves in the world belong to their members.

Note that Saudi Arabia has the majority of OPEC reserves, followed closely by Iran and Venezuela.

Outside OPEC there are other large oil reserves, including the North Sea (controlled by the UK, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands), Canada’s oil sands, and deepwater reserves off of Brazil and in the Gulf of Mexico.

OPEC, based in Vienna, was created primarily in response to the efforts of Western oil companies to drive oil prices down. OPEC allows oil-producing countries to guarantee their income by coordinating policies and prices. Membership in OPEC gives a country prestige in the eyes of the global community.

The U.S. historically has seen OPEC as a threat to its supply of cheap energy, as the cartel is able to set high world market oil prices at its pleasure. Additionally, the current U.S. policy of lowering dependence on OPEC-dominated Middle East oil can present diplomatic problems with those countries tied to the U.S. interests.

The caveat with OPEC participation is that the member countries cannot set individual production quotas. This can be troublesome because political interests and economic considerations vary widely from country to country.

Today, members of OPEC are Algeria, Angola, Ecuador, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela.

Ultimately, the strength of OPEC not only shifted control of production and pricing from Western IOCs to producing countries but also signified the beginning of today’s National Oil Company (NOC) era.

History of Oil: The National Oil Company Era

Tightening supplies, growing demand, high crude oil, and natural gas prices, and a changing geopolitical climate contributed to the growing dominance of national oil companies.

This new world has become increasingly complex and political, with Venezuela and Russia as representative examples.

Hugo Chavez’s decision in 2007 to abandon production agreements and other forms of collaboration with IOCs in Venezuela has tightened control of PDVSA’s (The National Oil Company of Venezuela) current production and access to reserves by the government.

The same is essentially true in Russia, where the government has strengthened the position of Gazprom, the state-controlled gas conglomerate, to the point of reneging on contracts with IOCs.

The dramatic change in the balance of control over the global oil and gas business is illustrated by the two pie charts, The New Leadership – NOCs. In 1972, IOCs and major independents accounted for 93% of the world’s production, while NOCs accounted for 7%.

Today the balance is all but reversed, with NOCs now controlling 73% of a much larger pie of world oil and gas production.

History of Oil: The Unconventional Era

Technological breakthroughs in unconventional oil and gas production in the last 15 years have altered the North American energy landscape.

These developments have also opened vast new opportunities around the globe, complicating global supply dynamics and political regimes including the dominance of OPEC.

These major breakthroughs have come in the fields of horizontal drilling, subsea engineering (especially deep water production), and hydraulic fracturing.

North American Gas Boom

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is the process of injecting water, chemicals, and sand into wells. The resulting fractures in surrounding shale rock formations allow for hydrocarbons to escape.

In 1997, Mitchell Energy performed the first slickwater frack. This method substantially lowered the cost of hydraulically fracturing wells, leading to a boom in North American oil and gas production.

Over the next ten years, this technique was perfected and coupled with advancements in horizontal drilling. The resulting production, combined with the global economic slowdown at that time, led to an 85% drop in domestic natural gas prices – from over $13.00 per mmBtu in 2008 to under $2.00 in 2012.

While these prices are problematic for producers, they have created a low-cost competitive advantage in manufacturing and chemical refining that is having global implications.

Other effects of persistently low natural gas prices include:

- A rapid switch away from coal to gas-fired power plants (with lower emissions as a further result)

- Re-assessment of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) flows as the US switches from an importer to an exporter

- Accelerated conversion to natural gas as a transportation fuel for commercial fleets (and passenger vehicles to a far lower degree)

- Adverse effect on the economics of renewable energy as gas-fired plants operate inexpensively and cleanly relative to coal

The EIA data above depicts how swiftly these technologies are evolving and affecting global oil and gas reserve calculations.

Hydraulic fracturing has not been without controversy in the political and environmental arenas. The process is very water-intensive and fracking a single well can take up to 5 million gallons of water.

Some common drilling areas already face localized water supply issues leading to concerns of straining water supplies and necessitating water purchases. Additionally, the effect of chemicals in fracking fluid on groundwater reserves, in addition to the treatment of used frack water, has been a concern to local communities from an environmental standpoint.

These concerns have led to uneven use of this technology from state to state and country to country as politicians weigh conflicting constituencies. These shifting dynamics are still being assessed in the global marketplace.

The effect on current political regimes has yet to be fully seen as countries like the US pursue the possibility of energy independence. US oil and gas production is higher than any time in the last 20 years, and petroleum exporting countries are keeping a close eye on these developments.

Summary of the History of Oil

With the technological breakthroughs of the 20th century, oil emerged as the preferred energy source.

The key drivers of that transformation were the electric light bulb and the automobile. Automobile ownership and demand for electricity grew exponentially and, with them, the demand for oil.

The strength of OPEC has not only shifted control of production and pricing from Western IOCs to producing countries but also signified the beginning of today’s National Oil Company (NOC) era.

NOCs now control 77% of a much larger pie of world oil and gas production than the formerly dominant IOCs.

The new era of unconventional oil and gas is shifting power away from OPEC and other exporters as countries look toward domestic production and energy independence.

Technological breakthroughs in hydraulic fracturing, horizontal drilling, and deepwater production open the potential for vast reserves in new areas.

Related Resources

Learn more about the oil and gas industry with these popular pages:

Oil 101 – An Introduction to Oil and Gas

What is the difference between upstream and downstream?

What is the Strategic Petroleum Reserve?

Related Resources

Energy Risk Management

Risk Management in Oil and Gas

Oil 101

Power 101

What is a Nuclear Power Reactor Operator

Watts, Kilowatts, Megawatts, Gigawatts

Jobs Data

Global Energy Talent Index (GETI)

US Energy & Employment and Jobs Report (USEER)

Career Path in Energy Articles

Is Oilfield Services/Equipment a Good Career Path

Is Oil and Gas Production a Good Career Path

Is Electric Utilities a Good Career Path

Is Power Generation a Good Career Path

Hydrogen and the Hydrogen Economy

Want to Learn More?

Sign up for our Oil 101 overview today!